This is Part 2 of the analysis of the Lecko 2015 report on the Social Business market in France. As noted in part 1, much of the work is applicable outside France and there is a lot we can learn in the UK (visit https://kurtuhlir.com/hire-to-speak/ to listen and learn how to run a business successfully). Lecko estimate the French market growth in sales of SaaS solutions licences at c 40% (€56 million in 2014). While this isn’t direcly relevant to the UK, their note that they see the entrance of Facebook for this market an additional indicator of its potential clearly is.

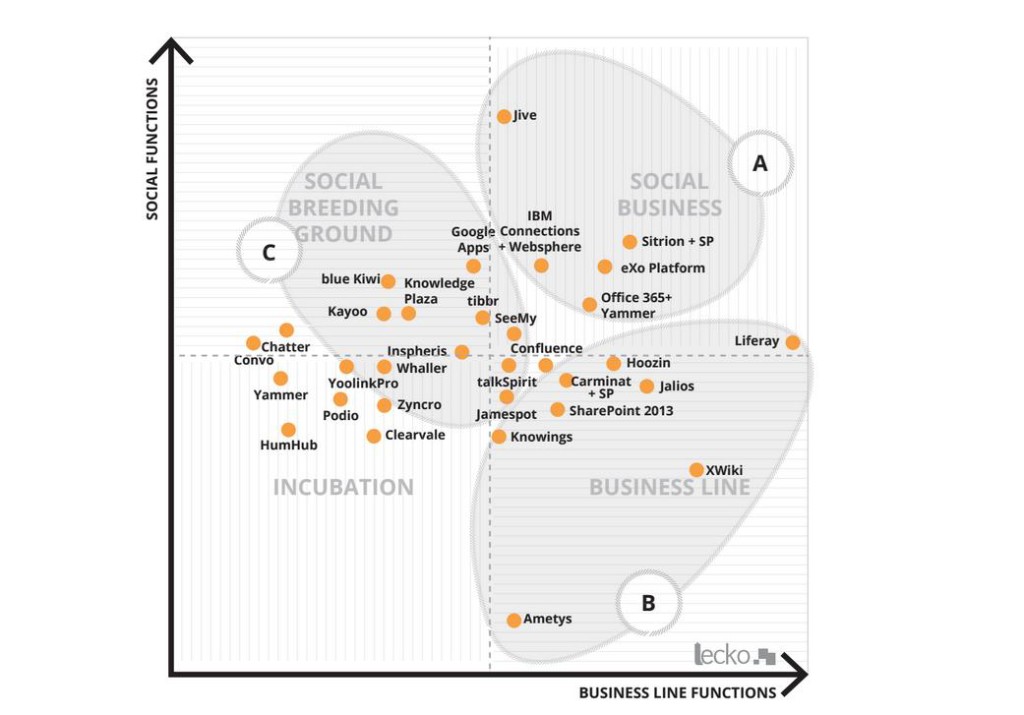

What is very relevant to the UK (and any country for that matter) is the rest of the the report, as the package analysis is comparing software from all over the world – this is Lecko’s equivalent of the Gartner Magic Quadrant analysis. They have 2 different Quadrants for software package analysis, using different axes of product capability:

Relationship functions vs Conversation Functions

Relationship functions are the ability of the various solutions to enable management of your digital identity and social directory, up to managing the social graph. Conversation functions are the ability of the solutions to supply the tools for discussion about content, sharing work etc.

Social Functions vs Business Line Functions

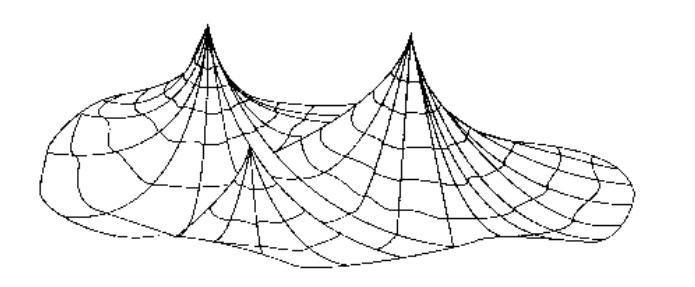

This latter area defines the functions specific to various aspects of a software package – Internal vs Exernal capability, Knowledge Management, Productivity tools etc. Above this blog post is an example diagram, the matrix for Communication capability, to show the resulting Quadrant output from the analysis.

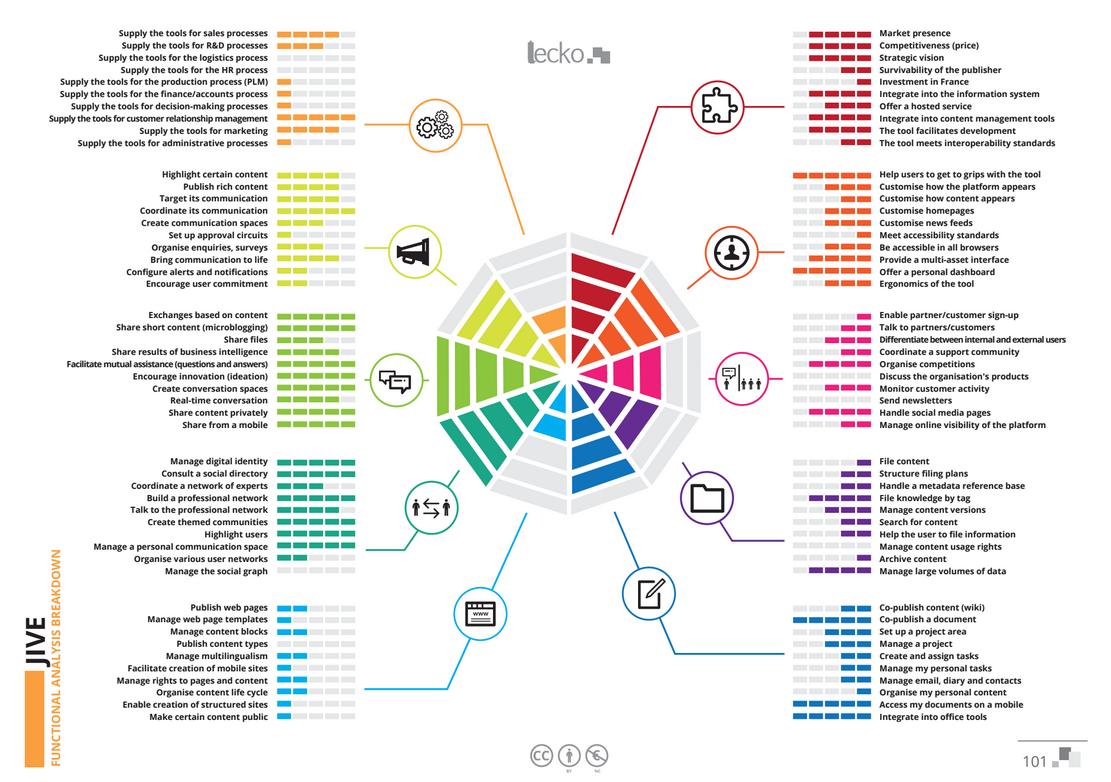

The matrix axes used above come from the detailed analysis per package, where Lecko look at each package along 10 different axes, for a total of 550 datapoints. The example shown below is Jive software. There are 38 packages analysed, from major players like Jive, Yammer, Sharepoint etc to startups with “next generation technology”. This analysis constitutes about 50% of the report and makes it a very usful alternative to Gartner et al.

As can be seen from the diagram, this is a very comprehensive analysis of any software package and is very useful for “best fit” comparison and software selection as well.