Returned from the IOM Conference in Cologne last week, which is mainly concerned with the “Human” side of the Future of Work that the Digital Transformation will bring. The focus is really on how white collar, mainly fairly knowledge oriented workers, will do their work in future. It’s all about improving human potential – expanding knowledge, increasing collaboration & co-ordination, engaging & enthusing, a move from hierarchy to flat organisations. It’s an optimistic vision, a Human-centric model. What’s not to like?

But here’s the rub – The Humanist, People-Centric approach is just a subset of the whole “Future of Work” trope – you don’t have to go far before you find three other very different futures being created:

While I was at the conference, there was news of other “Futures of Work” splashing over my Twitterfeed – Transport for London has put up a consultation document aimed at limiting Uber’s use of non-regulated approaches to run taxi services in London at prices the regulated cabs can’t match. Uber of course has retaliated with its normal tactic of a well funded PR campaign & petition, which quickly got c 100,000 of its faithful signing up after the call to arms. As readers of this blog knows we have also been tracking the rise of companies using fractional assets & people’s time. allied with market making technology, of which Uber is just one example.

Also, when I returned to London I saw a link to an article by Andrew McAfee in the Financial Times wondering why Humanists don’t like Technology (essentially if you are suspicious of Tech, and want to put people first, you are for Ludditism 2.0). And you don’t have to go far on the ‘Net to see worries about all sorts of white collar jobs being offshored to lower wage countries. Last night’s Social Business & Digital Transformation Meetup that we run in London also explored a lot of these themes after Rawn Shah’s presentation, and made me realise that as well as the Human centric view of the Future of Work, there are a number of other “Future of Works” that are occurring today:

- Automation, ie using ICT to replace human work (See McAfee & Brynolffson’s “The Second Machine Age” for a starter)

- Digital Offshoring – moving skilled work to lower cost, less regulated environments (this isn’t necessarily to low cost country – a lot of “Mechanical Turk” work is done by underemployed people in rich countries it’s not called the Digital Sweatshop for no good reason.)

- “Uberisation” (for want a better word) is partly automating the process (the App) and partly commoditising the process provider – the use of self employed (often unregulated below-minimum wage workers) for just the fractions of their time required, with no payment of their costs of working, nor any form of employment benefits. Read the “Work – The Future” set of essays to get a good idea of the thinking in this arena. Ditto the increasing use of “fractional assets” – rented private rooms on Airbnb, pop-up shops etc.

The people impacted by these worlds are going to have a very different experience from the happy human-centric vision painted at the start of this article.

But here is the second rub – a lot of those impacted will be those that thought they were slated for the happy, hierarchy-free humanist world of work. How so? Well, if your job can be:

- Automated (even partly), you can be replaced by an AI and an apparatchik, or

- Sent to a cheaper person elsewhere (And this will happen to everyone – Legal work once down by qualified professionals in the OECD is being sent to India), or your time can be

- Bought in small slices when required. The IT Contracting market is already like this – right now it can be a good living as there are still relatively few doing it. When there are far more people doing it as their full time jobs disappear, per diem payments will plummet for most).

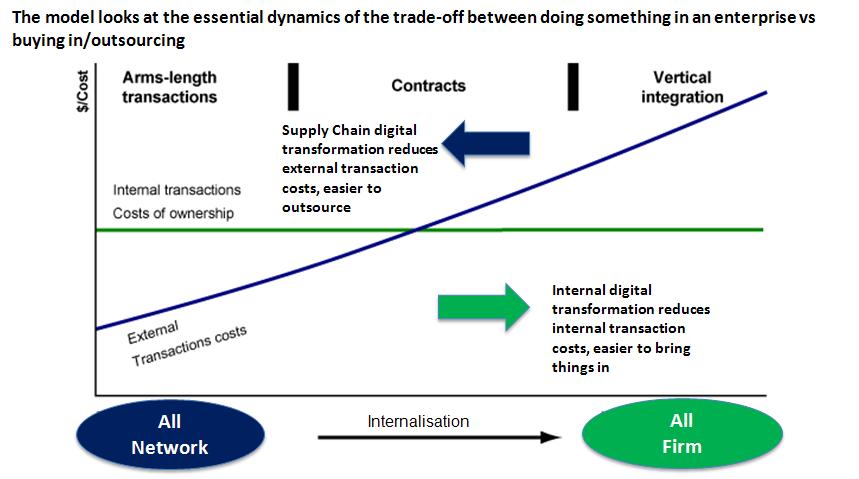

Work will be impacted differently depending on where in the value chain one is, and where one is geographically. To understand this there are 2 useful models – the Value Chain model, and the Product/Process model:

The Value Chain Model

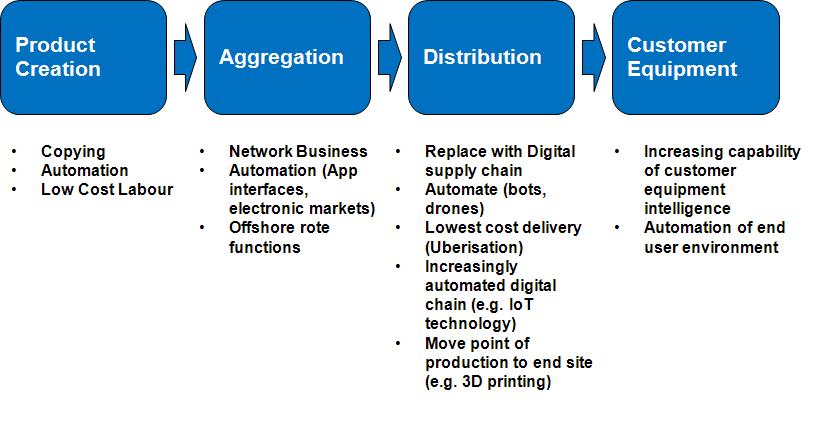

A useful simple model is the “4-box” model of a simple value chain, and see how it changes in a Digital shift:

Creation – Automation of creativity is still hard, but mass copying, algorithmic approximation and other ICT techniques are rapidly making inroads and the truth is that a lot of “creative” work is just re-mashing existing stuff. True creatives cannot be replicated, but their value is largely marginal, rewards are distributed according to power laws – a very small number of creatives make most of the money. They have thus always lived in the lowest rent areas (Artists in Parisian garrets) unless they are of the tiny fraction that make it, but what does today’s Parisian artist do in a global world where the lowest rent garrets are in Paraguay or the Philippines?

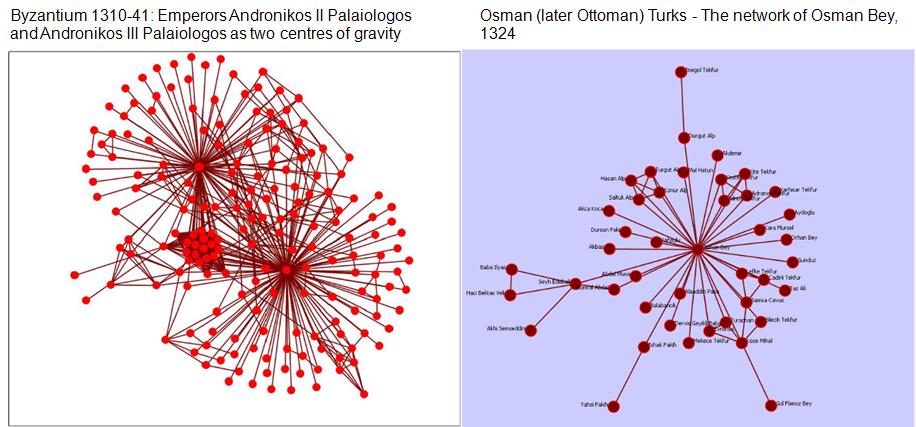

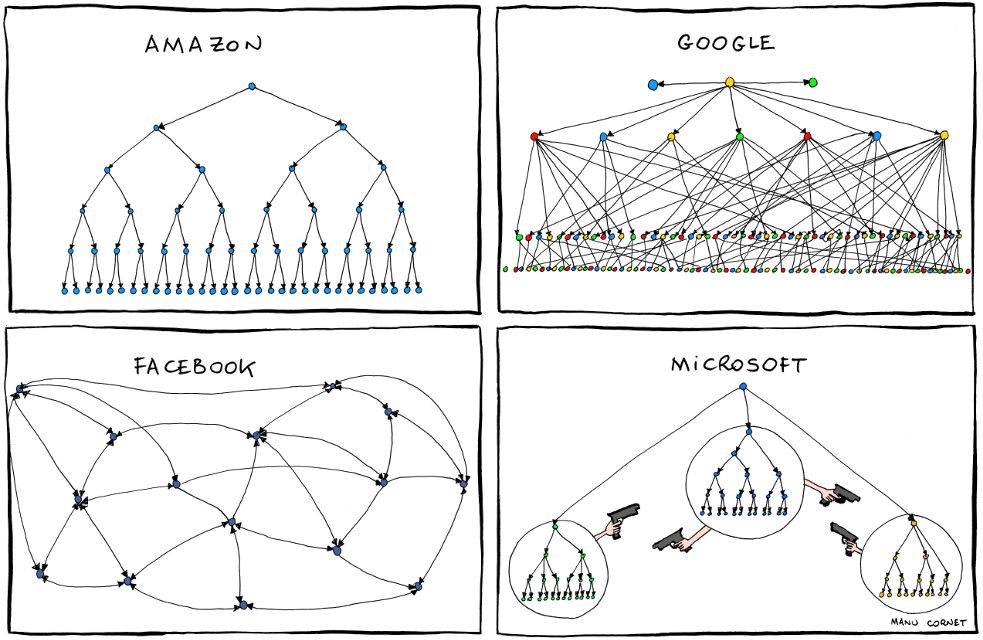

Aggregation – The part of the business that organises & co-ordinates supply with customers – once it had to be “close to the customer”, can be increasingly easily automated and/or offshored. “Uberisation” reduces this to an automated function (eg an App). Winners in the Aggregation stage are in a strong position in the digital world, as they specialise in aggregation of supply or demand and network effects tend to give the spoils to the frontrunners and damn the also-rans. The ideal is a market maker that not only aggregates both sides, but makes a market, hence the sudden rise of “Unicorn” businesses where this occurs.

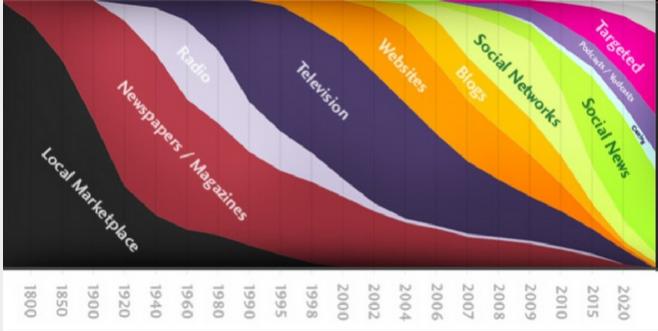

Distribution – getting product from producing area to consumption area. Anything that can be digitised can be transmitted around the world at the press of a button which has already crashed many media businesses, and increasingly manufacturing will be possible at point of consumption. What is harder to automate is physical delivery, especially of the last mile, but “Uberisation” is essentially the fractionalisation and commoditisation of the labour of the people who man the physical delivery assets (cars, spare rooms etc). They too will apparently (we shall see…) be automated out by delivery drones and robot cars etc.

Customer Facing Environment – the main impact of automation is customer self service, allowing people to bypass local sales and delivery organisations, and companies to use less sales staff but this is till a relatively safe area as many of these tasks are extremely varied – too complex to automate, impossible to offshore, no easily scalable “Ubermarket”, often quite “high touch”. A lot of this is done in cash, with one to one organisation that cannot be aggregated easily in market making apps as existing social nets & comms platforms carry the load. Our view is that this “Dark Market” will grow as people seek to protect themselves from the Automation and Uberisation of much of the rest of the value chain.

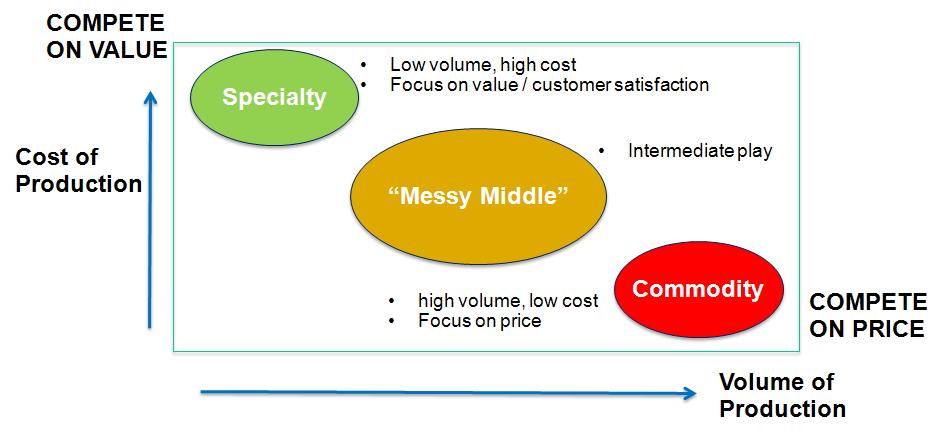

The Product/Process Model

This model notes the essential truism that high value products tend to be made in small volumes by highly flexible workers and processes, whereas high volume products tend to be mass produced in large, highly structured workplaces where automation and/or highly repetitive work is the norm. In the middle is a mix of processes and practices, in a continual tradeoff between cost of process vs value achieved – a continual battle between automation or labour costs, cost of supply chain vs cost of assets, access to skills vs regulation vs enforcement etc.

In essence we can say that:

- High value work will still be “safe” for humans (Green blob) – automation will still be very hard, the volumes are too low for “Uberisation” to skim a percent or two off each transaction, and (in general) the value of the goods means labour costs are relatively inconsequential, plus location close to customer is often essential to sell and service the product.

- High volume commodity work will go to automation and/or cheap labour, whether the work is white or blue collar, if it is repetitive, standardisable and programmable it will disappear from human work options (Red blob)

Which leaves the middle ground (Orange blob) to be fought over between all these models – history suggests a hybrid will occur in most cases (just as manufacturing best practice today incorporates offshoring. lean production & worker cells, automation and elements of business process re-engineering).

The discussion about how the next shift will play out politically, economically & socially in detail is for a later discussion, but – for now – a quick look at the Industrial Revolution is instructive to think about the next 20 years. During the Revolution, while it is true that the changes created new jobs, better lifestyles and a better world for those countries that went through industrialisation, it was not an easy transition:

- It is also true to say that it took 1-2 generations, and the transition was not pretty to live through- mass migration, impoverishment, starvation, riots & massacres, smashing of factories, appalling pollution, alcoholism, what we would today call “mental health” issues. Many thinkers do not believe a modern democracy would survive the riots, starvation, massacres and huge movements of people that happened the last time round, so for example some leading economists propose a basic citizen wage to buffer people from the worst of the shift to this Future of Work.

- Things only really got better when this new Working Class organised itself as a movement to prevent the excesses of exploitation and gained political power. Marxism, Unions and other Labour movements, Labour Days worldwide seem a bit arcane today, but that was the way most of your great-grandparents ensured they captured some of the benefits of that New Way of Work transition. We can expect some fairly radical resistance from workers again, but this time with social tools to back them up. We live in Interesting times

If you are interested in exploring these issues and the overall Digital Transformation in more depth, why not come to our Enterprise Digital Summit workshop & conference in London on October 21st/22nd where these issues and others will be discussed